While the wine trade enjoys a romantic public image, it is a business, and a cutthroat one at that. And, like any other business, it has had its share of unscrupulous operators. The first fraud involving wine probably arose shortly after it was initially recognized as a valuable commodity many thousands of years ago, and the ensuing years have only seen the schemes grow more ingenious, even as more controls have been put in place to stop them.

The history of scandal in the wine business is not only long and colorful; it also has much to say about our complicated relationship with this complicated beverage. Wine may be the most regulated drink in the world, and yet it remains surprisingly easy for knaves and scoundrels to exploit our fundamental gullibility, credulousness, and insecurity about it.

While the permutations of wine frauds and scandals have been nearly limitless, I think they can be sorted into three general categories: wine adulteration, brand fraud, and collector fraud.

Adulteration

The simplest form of wine fraud is adding foreign substances to a wine in order to disguise flaws, lower production costs, or both. While in theory this is also the easiest type of fraud to detect and prevent, it has a long and seedy history.

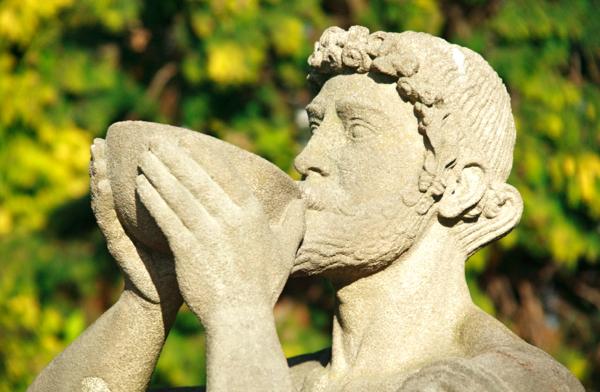

Wine adulteration goes back at least as far as ancient Rome, where it was a common practice for wine merchants to boil grape must (the unfermented juice and skins) in lead cauldrons and add the reduced must to their finished wines. The high levels of lead acetate in this concentrated must had the effect of both sweetening the wine and preserving it. Although the health effects of ingesting lead were well known even then, Roman nobility drank oceans of the stuff; lead consumption has been linked to the sterility of Caesars Julius and Augusta and the dementia of Nero, among many other leaders of the late Roman Empire.

The practice of adding “sugar of lead” to wine remained common through the Middle Ages — despite royal edicts prohibiting the practice and even making it punishable by death — and sporadic well into the 19th century, contributing to an extraordinarily high level of chronic lead poisoning among wine drinkers (i.e., most European adults) for hundreds of years.

A more recent episode of adulteration was the notorious “Austrian antifreeze scandal” of 1985. A number of producers of sweet wine in Austria, faced with three bad harvests in a row and contracts to keep, resorted to adding the chemical diethylene glycol (DEG) to enhance the impression of sweetness and body in the wines. DEG is toxic in moderate doses, and it has been the source of a number of deadly incidents over the years, including a 1937 drug incident in the United States that killed 105 people and gave rise to the modern FDA. (Remember the 2007 Chinese toothpaste scare? DEG again.) More than 36 million bottles of tainted Austrian wine were destroyed by the authorities, used as road de-icer and as fuel for power plants.

No one got sick or died from the contaminated Austrian wines — in fact, the levels of DEG in the wines were so low that you would have had to drink dozens of bottles over the course of a week or two to see any ill effects — and only a relatively few producers in a few regions were implicated in the scheme. But the terrifying “antifreeze” media reports, combined with the slow reaction of the bureaucratic authorities in Austria and Germany (the primary importer of the wines), caused consumers to run from all Austrian wine. Despite some predictions at the time that the whole incident would be forgotten in a year, the Austrian export market immediately collapsed and did not recover for more than 15 years, long after the Austrian government implemented one of the strictest wine quality laws in the world.

These are extreme and obvious examples, but in the more day-to-day wine trade there is a fine line between illegal adulteration and perfectly legal “modification” of wine. For example, the addition of brandy to Port to preserve it during ocean voyages was originally considered adulteration, but it became so widespread (and was so successful in its goal) that it eventually became the norm.

Similarly, chaptalization — the practice of adding sugar to fermenting grape must in order to increase the alcohol level of the finished wine — is considered illegal adulteration in Germany and Italy, but is common practice in Champagne and is permitted in many other winemaking regions, including Oregon and Long Island. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration permits the use of many other additives that you might think of as adulterants, including potassium carbonate, tartaric acid, copper sulfate, and bentonite — none of which have to be disclosed on the bottle.

Outside of poisons and other clearly harmful substances, what constitutes adulteration really depends on your fundamental view of what wine is supposed to be. The growing crop of “natural wine” enthusiasts take the Platonic position that wine is only grapes and indigenous yeast; anything else is an adulterant. Those who view wine as a beverage created by the hand of man — a product that should be shaped by its makers to provide a particular taste or experience — will be much more tolerant of additives and manipulations. It’s a philosophical debate that will probably last as long as we continue to drink the fruit of the vine.

Next up: Counterfeiters and brand thieves!

Mike Healan grew up in a teetotaling family, and had his first taste of booze — a Bartles & Jaymes wine cooler — at age 22. He has spent the years since then making up for lost time. After fifteen years making people miserable as an attorney, he is now doing penance by making people happy in the food and beverage business. When not immersed in the world of wine, he enjoys world travel, staring contests with his dog, and eating copious amounts of cheese. He writes from the SGT East Coast regional headquarters in Boston.

Mike Healan grew up in a teetotaling family, and had his first taste of booze — a Bartles & Jaymes wine cooler — at age 22. He has spent the years since then making up for lost time. After fifteen years making people miserable as an attorney, he is now doing penance by making people happy in the food and beverage business. When not immersed in the world of wine, he enjoys world travel, staring contests with his dog, and eating copious amounts of cheese. He writes from the SGT East Coast regional headquarters in Boston.