I have a confession to make: Before a few months ago, when I sat down in the Sabathani Community Center's auditorium to hear my fellow neighbors voice their concerns and ask questions about the Seward Co-op's second location tentatively set to open on 38th and Clinton, I had never attended a community meeting. For all my desire for community closeness and professed interest in local issues, this was the first time I actually joined in on an open discussion about my immediate community’s future.

This particular meeting sparked my interest for two reasons: one, I’ve worked a food co-op in Minneapolis for almost nine years; and two, I’ve lived in the Powderhorn neighborhood for over three years. I prefer to buy most of my groceries at the co-op where I work, but on odd days off when I need to grab some salad greens for a friend’s dinner party, say, the two-hour roundtrip bus ride to procure said greens really brings home the reality of a food desert. Throw in two small children and several heaping grocery bags and I’d imagine you’d have the stuff of nightmares. So the prospect of a co-op in the area seemed like it would be desirable to families in the area, as it was certainly desirable to me, but I was curious to hear everyone’s unique perspective on the project.

The crowd at the community meeting

The crowd at the community meeting

Nearly three hundred people joined in on the discussion on July 9th about Seward Co-op’s proposed second location on the block which the Greater Friendship Missionary Baptist Church used to call home. The congregation moved down the street a while ago, but Seward has retained part its name for the proposed location, coining it the “Friendship” site Along with Seward co-op, the grassroots neighborhood nonprofit group, The Carrot Initiative, hosted the event at Sabathani. The Carrot Initiative formed with the goal of “bringing a full-service grocery store to the West Powderhorn neighborhood,” and after weighing other options (such as approaching stores like Trader Joe’s and even starting a co-op themselves) they partnered with Seward.

Many of the attendees at Sabathani arrived ready to support the project, excited that the new Seward will provide fresh, healthy food their neighborhoods, all under-served communities. Yet not everyone was sold on the idea of a co-op, especially one arriving from another neighborhood. Overall, what community members seemed to want to know was: Whom will this co-op be for, really?

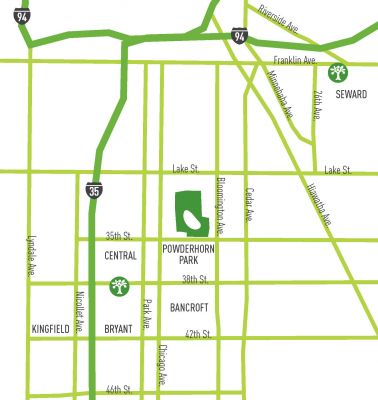

The location of the proposed co-op is marked in the lower left quarterOne of the major concerns

voiced during the community meeting is that the store will constitute a “white

space,” an environment where only white residents feel included,

represented, or even welcome. One audience member pointed out that the panel

onstage at the community forum, which consisted of Seward employees and board

members, city councilwoman Elizabeth Glidden, Pastor Billy Russell of the

Greater Friendship Missionary Baptist Church, and Carrot Initiative board

members, failed to represent the diversity of the neighborhood.

The location of the proposed co-op is marked in the lower left quarterOne of the major concerns

voiced during the community meeting is that the store will constitute a “white

space,” an environment where only white residents feel included,

represented, or even welcome. One audience member pointed out that the panel

onstage at the community forum, which consisted of Seward employees and board

members, city councilwoman Elizabeth Glidden, Pastor Billy Russell of the

Greater Friendship Missionary Baptist Church, and Carrot Initiative board

members, failed to represent the diversity of the neighborhood.

Eric Weiss, Carrot Initiative board Vice President, responded in part by announcing that two seats on the board were currently open, that the organization was accepting applications, and those that felt they could speak for the community were encouraged to apply. These board seats hold the potential to provide valuable checks and balances on the project, as the Carrot Initiative asserts in its FAQ about the Friendship store that it “will remain an autonomous partner in this process and plans to continue to engage and advocate with and on behalf of the community.” It appears that the call for applications worked, because instead of adding just two new board members, last week the Carrot Initiative announced the names of eight new community members who will now sit on the group’s board.

Community members also wanted to know if the Friendship store will be a place where low-income residents will be able to shop. The idea that co-ops are too expensive remains a perennial barrier, whether perceived or real. Evidence exists that for many purchasing the bulk of a household’s food at a co-op is possible, but available time, family size, and education all play a role in the equation. The reality is that, in many instances, co-ops do cost a little more. Co-ops must keep prices higher than some of their competitors for a variety of reasons: organic, small-scale food is more costly to produce; co-ops want to offer producers and distributors a fair price for their products; co-ops don’t have the wholesale buying power of a large chain grocery store; co-ops want to pay their own workers a living wage and provide generous benefits; and co-ops want to make at least some profit, so that it can be shared with workers and owner-members.

The old Seward Co-op and the new one

The old Seward Co-op and the new one

Seward Co-op has strived to make their store as affordable as possible for shoppers. Already they offer a five-percent need-based discount, as well as a needs-based membership program, classes on how to shop the co-op on a budget (also check out SGT’s Co-op on a Budget series), and they accept SNAP and WIC. Seward also carries conventional food choices, which are usually lower in price. Families in the Bancroft, Bryant, Central and Powderhorn Park neighborhoods may be unable to buy all of their groceries at the new Seward Co-op, but at least they will have option of walking to the store to grab fresh greens to eat with dinner.

Even beyond those concerns, I think those of us who have been shopping or working at co-ops for a long time tend to forget how daunting it can be to enter into the world of food cooperatives. It can be difficult to know what to expect. I recall that when I was applying for a position at the Linden Hills Co-op years ago, I naively asked my then-boyfriend, “Do you think it’ll be okay if I wear leather shoes to the interview?” I was worried my choice of animal skin footwear might put off my, presumably vegan, potential employers. My boyfriend looked at me like I was crazy. Many shoppers enter a co-op unsure that they can spend their money there if they’re not members. Customers come in to the Linden Hills Co-op all the time and, heads slightly bowed, timidly inquire, “Can we shop here even if we’re not members?” “Of course!” we exclaim, “Welcome, welcome!”

A rendering of the second Seward co-op, with "Everyone Welcome" awning

A rendering of the second Seward co-op, with "Everyone Welcome" awning

The “Everyone Welcome” sign that sits above the door at most co-ops holds a double meaning: it declares that non-members may shop at the store, and it also generally extends an invitation to anyone that wants to shop there. However, what I heard residents of the Bancroft-Bryant-Central-Powderhorn Park area say at the community meeting is that before the Seward Co-op tacks up their “Welcome” sign in the neighborhood, the store should wait for the community to invite it in.

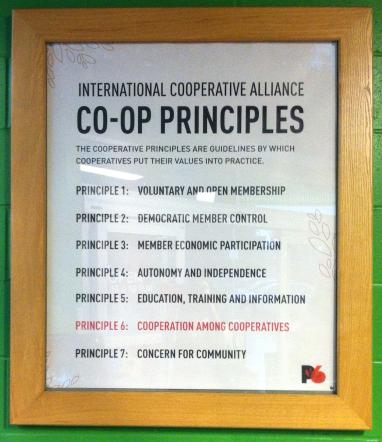

Ideally, a co-op reflects its environment because a community is what the

enterprise exists for, not a handful of shareholders looking to make a profit.

The last of the 7 Cooperative

Principles adopted by the International Co-operative Alliance states that “cooperatives work for the sustainable development of

communities through policies and programs accepted by the members.”

Along with dedication to responsible environmental and social practices, food

co-ops aim to serve shoppers’ needs. Therefore, as a co-op develops, the

community molds the store’s own unique product mix, education opportunities,

and events. An engaged community and membership can only create a store they

feel they own, and not just in the stockholder sense.

Co-op principles, posted at the Seward Co-op

Co-op principles, posted at the Seward Co-op

At the Sabathani meeting, I heard residents not so much voice opposition, but provide healthy skepticism for the project, and therefore present necessary challenges to both Seward and the Carrot Initiative. I believe this engagement bodes well for the new store. Although I came to meeting with a bias toward co-ops, my neighbors’ passionate concern about what a co-op would mean for the area’s future invigorated rather than disheartened me.

My first community meeting proved a humbling experience, for, as one by one members of the packed audience each stood up to offer their varied perspectives on the proposed project, it grew clear that many of these residents had been fighting for the health and vibrancy of their communities for a long time. What's more, they had been fighting for the option of good food for everyone in their communities for a long time. One of the audience members at Sabathani spoke up to object to her neighborhood’s designation of a food desert, pointing to the community garden that she worked in as an example of the fresh produce that can be found there. Other residents acknowledged the value of access to quality food from a co-op, but shared their fear that, that access would come with high cost of gentrification.

The Seward Co-op assured the crowd at Sabathani that the discussion about the Frienship store was only just beginning, and that the project was still at an early stage. Both the Carrot Initiative and the Seward Co-op promised tthe Sabathani meeting was only the beginning of a series of forums that they will host before the store on 38th and Clinton opens its doors. Since then, many individual neighborhood associations have met about the Friendship store, even outside the Bancroft, Bryant, Central and Powderhorn Park neighborhoods. Most recently, the Field-Regina voted to back the Carrot Initiative in its mission.

I’ll see you at the next community meeting.

Kelly Kassera grew up in Western Wisconsin, but has been happy to call Minnesota her home for over a decade. She works in the Wellness department at the Linden Hills Co-op. Her passions include reading and writing poetry, environmental writing, and food justice. When she’s not writing or talking about fish oil at the co-op, you can find her east over the border kayaking, drinking beer, and eating cheese curds. This is her first article for SGT.