Quick, think of your favorite comfort food. Is it the green bean casserole at Thanksgiving, or Chicago style pizza, or dim sum?

Now think about why it is a comfort for you. Is there a nostalgic memory of the happy dinners your family shared on a particular holiday, or does your comfort food bring you peace after a stressful day?

Once I was old enough to use a stove my dad taught me how to make biscuits and gravy, using the method he’d learned from my grandmother. Divorced from my mom when I was two, he wasn’t a Brady Bunch dad, and our conversations were sparse. Handing down the B and G (as we called it) was not just about putting breakfast on the table but it was also a feeling he wanted to give me, kind of like an emotional heirloom. Each time I make B and G, I feel a sense of connection to my father.

My favorite comfort food is my mother’s potato soup. (link to recipe) Whenever I was sick as a child my mother would put on a pot of potato soup. She sautéed onions and celery in butter, filled the pot with milk and potatoes, and then simmered it all with a bay leaf for about 30 minutes. In the time it took to simmer she would make a little bed for me on the couch, turn on the radio, and shortly thereafter I’d be spooning steaming soup into my mouth and feeling better.

Now I am a mom and when my little girl starts to get that hollow-eyed look that tells me a cold is coming, I go to the kitchen and start making chili -- with macaroni noodles, if she’s feeling particularly puny.

I doubt she cares whether the chili has significant healing properties, though it does. She is soothed knowing her mom is in the kitchen, making something warm and familiar for her. I remember that feeling when my mom cooked for me: cared for, protected, loved.

Lately I’ve been thinking about how we use food to communicate when words just won’t do. Providing a meal or plate of oatmeal scotchies communicates our desires, our sympathy, our triumphs and our joy. We show concern for a friend by dropping by with a homemade pie, and teach our kids about tradition with Sunday night dinners. We celebrate holidays, observe religious occasions and meet new neighbors with food. In my case, I am learning about an entire country through food.

For the past three

years I’ve been working with refugees from Burma on an intriguing urban farm

project in Fort Wayne, Indiana, called the Fresh Food Initiative. The project's goal

was to teach them to grow food on American soils, either to feed themselves, to

make money through agriculture or both. Growing food alongside our clients, I

learned very quickly that they could teach me as much as I could offer them.

For the past three

years I’ve been working with refugees from Burma on an intriguing urban farm

project in Fort Wayne, Indiana, called the Fresh Food Initiative. The project's goal

was to teach them to grow food on American soils, either to feed themselves, to

make money through agriculture or both. Growing food alongside our clients, I

learned very quickly that they could teach me as much as I could offer them.

Most of the folks that arrive in our neck of the woods had been living in refugee camps along the Thailand-Burma border for ten to fifteen years, where plywood huts and plastic tarps comprised their living quarters, with mountains and jungle forming their yards.

Amidst this desolation, a refugee assistance group bestowed an ironic and hopeful gift: seeds and some basic gardening information. With little else to do in camp those who could took the seeds, scratched out a plot in the dirt, and planted beans and faith. And, as every gardener must, they waited.

On average, refugees live in these camps for ten years, some as many as 17. Eventually, they arrive in Fort Wayne, with very few belongings: clothes, paperwork and some seeds. At the local resettlement agency they learn about integration services in our community, including our Fresh Food Initiative.

The Fresh Food Initiative began in 2010, as a project of Catherine Kasper Place. As an advanced master gardener and lover of all things nature related, I was beside myself with excitement to be offered the role of director of Catherine Kasper Place. I imagined my staff and I guiding clients through the learning stages of growing: choosing the crops to plant, designing a plot, scheduling the tasks, and paying attention to frost dates and other weather factors. Though we did educate our clients on many of these topics, they were clearly talented growers, resourceful and diligent in the garden.

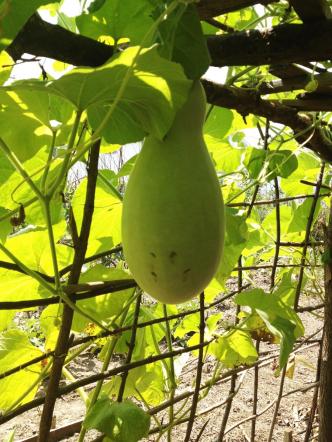

Opo gourdNow three years into

the program and still stumbling along trying to learn each other’s languages we

often find the best communication is food. When clients look out their windows

and see us on the farm, they walk over, balancing large bowls atop their heads

and carrying pitchers of 3-in-1, coffee pre-mixed with sugar and cream. They

smile and gesture for us to sit while they set up and distribute plates full of

rice, fish soup, opo tempura or if we are very lucky Laphet Thote, or fermented

green tea salad (note: there are multiple spellings for this dish).

Opo gourdNow three years into

the program and still stumbling along trying to learn each other’s languages we

often find the best communication is food. When clients look out their windows

and see us on the farm, they walk over, balancing large bowls atop their heads

and carrying pitchers of 3-in-1, coffee pre-mixed with sugar and cream. They

smile and gesture for us to sit while they set up and distribute plates full of

rice, fish soup, opo tempura or if we are very lucky Laphet Thote, or fermented

green tea salad (note: there are multiple spellings for this dish).

Our two Burmese staff interpret for us: you must put the fried nuts on top of the Laphet, or, dip the opo into the sauce. And we eagerly obey. Sitting on the ground, using our fingers to eat we laugh easily—them at the face I make when I overestimate the amount of chilies I can handle, and us as they double down and eat their chilies without breaking a sweat.

We are experiencing their culture through food, and I have learned several things from these meals:

- Like us, the Burmese enjoy a repeat selection of around six or seven dishes, unless they are celebrating. When celebrating they fix a good fifteen different dishes and you must ‘have a little bite of everything’, just as we expect at Thanksgiving. Approximately 50-70% of what they eat are vegetables. The most common of these include roselle (a leafy green member of the hibiscus family that tastes a bit like collard greens), long beans (related to but fancier than cow peas), Thai peppers (tip: do NOT underestimate these tiny cute war missiles), opo gourd, and tomatoes.

- A very communal group, the Burmese share food with everyone. The shared food is a blessing upon the receiver, much like an offering. Laphet Thote, a fermented green tea salad, is often the dish of choice to share because everyone has a slightly different way of preparing it, and each is wonderful. The addictive salad is very frequently served as a snack, like potato chips, for people to graze upon until the main dinner is served.

- In Burmese culture it is not polite (nor will it actually work) to say you aren’t hungry. If you cannot eat a full meal you must at least take a tiny bit and say that you have just come from dinner. My advice is to just give in, wear comfy clothes, and eat a second dinner -- you won’t be sorry. Once I took my daughter to a celebration at the Mon temple, and as we sat down she was inundated with bowl after bowl of unfamiliar food. Eyes wide, she encircled the bounty with her arms and dug in. She ate every bit of everything, and I am not sure who was beaming more, her or the friend who had invited us.

When you think about it, this nonverbal (unless you are me, constantly announcing, “This is so amazing!” with my mouth full) communication is a universal kind of storytelling. When my aunt taught me how to make her famous dish, including the secret ingredient, she gave me a gift, an expression of emotion that words cannot convey.

And, once you’ve tried these delectable Burmese dishes you will start to believe that if a picture is worth a thousand words, a shared meal is an encyclopedia of feeling.

Mom’s Potato Soup

Serves 4

Ingredients:

- 4 Yukon Gold potatoes, washed and cubed

- 1 medium onion, diced

- 2 celery stalks, diced

- 2 tablespoons butter

- ½ gallon skim milk

- 1 bay leaf

- salt and pepper to taste

Instructions:

- Sautee onion and celery in butter over medium heat until translucent.

- Toss in potatoes, cover and simmer for ten minutes.

- Add milk slowly, stirring to mix.

- Simmer all for 25 minutes.

- Add bay leaf, simmer for ten more minutes. Serve with a kiss.

Laphet Thote

For the Laphet (Fermented Green Tea Leaves)

Note: you can buy pre-packaged fermented tea leaves to save time

Ingredients:

- 4 cups hot water

- 1 cup organic dried green tea leaves, loosely packed

- 1 cup kale or green cabbage finely chopped or shredded

- ½ cup finely chopped cilantro, loosely packed

- ½ cup green onions, finely chopped

- 1 tablespoon garlic paste

- 2 tablespoons finely chopped ginger root

- 2 green chilies, minced (optional)

- juice squeezed fresh from one lime

- generous pinch of salt

Instructions:

- Pour 4 cups of hot water over the dried tea leaves.

- Stir and let soak 10 minutes.

- Drain, pick through the leaves, and discard any tough bits.

- Squeeze out any remaining liquid from the tea leaves.

- Put tea leaves in lukewarm water and mash with your hands.

- Drain and squeeze out extra liquid.

- Repeat this rinse once more, then add cold water and let stand for 1 hour.

- Drain, squeeze to remove excess water.

- Chop the leaves finely and mix together with kale, cilantro, scallion greens ginger, garlic paste, salt and lime juice.

- For an extra kick include 2 minced green chilies.

- Cover the dish tightly and allow it to ferment, untouched, for two days in a dark, cool space, like a pantry.

- After two days, place the container in the refrigerator and prepare the following crunchy mix-ins:

For the Salad

Ingredients:

- 3 tablespoons peanut oil

- 1 bulb garlic, all cloves thinly sliced

- 2 tablespoons sesame seeds, toasted and lightly crushed

- 3 tablespoons roasted peanuts, coarsely chopped

- 3 tablespoons roasted soybeans, lightly crushed

- 3 tablespoons roasted pumpkin seeds

- ½ cup thin tomato wedges (optional)

- 2 tablespoons dried shrimp, soaked in water for 10 minutes and drained (optional)

Instructions:

- Set a wide skillet over medium heat. Add the sesame seeds and let them heat, shaking the skillet from time to time to ensure that they aren’t scorching. You will start to smell them toasting after a few minutes. Keep stirring so they don’t scorch, and cook for another minute or two, until they are golden. Transfer to a dinner plate and let cool completely.

- Next, heat the peanut oil over medium-high heat, add the sliced garlic, reduce the heat to medium and fry until just golden, about 5 minutes. Lift the garlic out of the oil with a slotted utensil and set aside on a plate to crisp up. Save the oil, now flavored with garlic, to use in the final dressing (recipe follows).

Laphet Thote

Dressing

Ingredients:

- Reserved garlic oil

- 1 teaspoon fish sauce (optional)

- fresh lime slices

- pinch of salt

Assembling the Salad:

- Serve the salad unmixed, arranging small piles of all the ingredients on a platter.

- Toss the fermented tea leaves with the reserved garlic oil, a few splashes of fish sauce, and fresh squeezed lime juice to give an extra sour note.

- Add a generous pinch of salt, mix again, taste and adjust other seasonings if needed.

- Place the leaves in a neat pile in the center of the other crunchy mix-ins.

Holly

Chaille was raised in Bloomington, Indiana, spent seventeen years in Virginia,

and now lives happily with her husband and daughter in Fort Wayne, Indiana. A

tree hugging dirt lover since childhood, Holly’s passions are creating

community gardens in food deserts and planting pollinator gardens wherever she

can get away with it. She’s an advanced master gardener and writer currently

plotting her next adventure. This is her first article for SGT.

Holly

Chaille was raised in Bloomington, Indiana, spent seventeen years in Virginia,

and now lives happily with her husband and daughter in Fort Wayne, Indiana. A

tree hugging dirt lover since childhood, Holly’s passions are creating

community gardens in food deserts and planting pollinator gardens wherever she

can get away with it. She’s an advanced master gardener and writer currently

plotting her next adventure. This is her first article for SGT.