Often, when I mention our CSA to people unfamiliar with Community Supported Agriculture and I explain how a CSA works, they express astonishment at the high cost of these weekly vegetables. With each year of CSA participation, though, I feel less and less interested in justifying my choice. When someone asks, “Isn’t that really expensive?” I shrug and say, "it depends on how you look at it." Now, for people who want to argue the point further, I have a book to recommend.

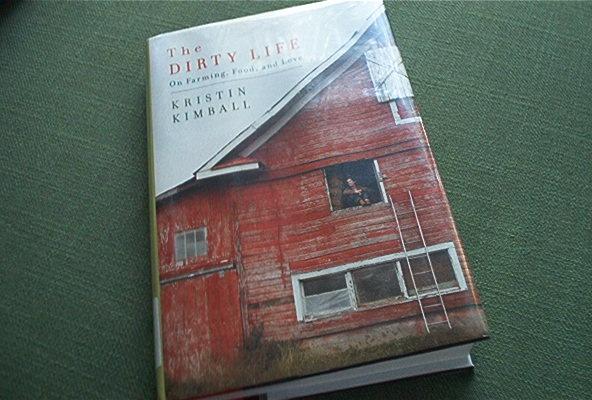

The Dirty Life (2010), by Kristin Kimball, tells two concurrent love stories: one between her and her eventual husband, and one between her and the farm they began together in 2003. When she meets Mark, she is a writer living in New York City while he is a farmer in Pennsylvania. She soon realizes that although “there were more cultural differences between Mark and me than there were between Mark and a random selection of taxi drivers from the developing world” (30), it is obvious that there is also an undeniable spark between them.

Soon, she has left her urban life for five hundred acres in Essex, NY, where she will discover that “as much as you transform the world by farming, farming transforms you” (5). On those acres, good land fallen into disuse, they begin to build “a farm from scratch, and the land was big enough, and good enough, to support anything [they] could dream up” (56).

What they dream up is something that I think any CSA member would find exciting. After time working on standard CSA farms, Mark had “been wondering what it would be like to tweak the CSA model a bit, so that, instead of providing a set amount of vegetables each week, our farm would produce a whole diet, available to members on an unlimited basis, just as it was available to us” (57).

Did your heart just catch in your throat? I know mine did as I read about Essex farm, where the 150 member families go year-round for forty different vegetables, fruit, meat, dried beans, herbs, dairy and eggs, honey, maple syrup, and more.

The price? “$2,900 per person per year” (4) – which sounds incredibly extravagant, but equals about $241/month. Still, as Kimball notes, “At the price we were charging, most people in our community couldn’t afford to use our food as a supplement to their usual grocery store haul. They’d have to give up, like I had, that familiar and comforting experience of pushing a cart down an aisle. The central question in the kitchen would have to change from What do I want? To What is available?” (161). A shift in questions that even a dilettante-level participation in locavore thinking will show can be more challenging to the modern person than we expect.

It can be easy to forget that being a CSA member is not just about buying vegetables (and whatever else your CSA might provide - recently we received honey with ours). It is also about supporting local farming, small farms, and the people who are doing “the dirty work” of growing food. There’s a reason why Kimball chose her title: “I had never in my life been so dirty. The work was always dirty, beyond what I’d previously defined as dirty…I had daily intimacy not just with dirt dirt but with blood, manure, milk, pus, my own sweat and the sweat of other creatures, with the grease of engines and the grease of animals, with innards, with all the stages of decomposition” (128).

One of the pleasures of The Dirty Life is Kimball’s description of the landscape, life, and work of the farm. Her vivid descriptions extend not just to the many varieties of dirt the farming life can feature but also give many insights:

- On the arrival of their first pair of draft horses: “They stepped off the trailer like kings. That such creatures exist moves me. That they labor for us, willingly and with heart, is miraculous” (88).

- On what the milking cow has to teach: “There is no better lesson in commitment than the cow. Her udder knows no exceptions or excuses” (91).

- On late summer on the farm: “When we walked the mowed margins of the fields in the evenings, a school of black crickets sprang ahead of us like dolphins in front of a ship. The pond behind the farmhouse had shrunk to half its size, and it was thick with frogs. Every afternoon, the great blue heron came, patience in the form of a bird. Still, still, and then a movement too quick to be seen. The heron had gigged a frog. The frog struggled at the end of the heron’s bill, and the heron tilted his wedge of a head to the sky, swallowed, and resumed his perfect stillness, one skinny chorus-girl leg cocked backward at the knee” (212).

And:

- On the rewards of all the hard, dirty, exhilarating work: “A farm asks, and if you don’t give enough, the primordial forces of death and wildness will overrun you. So naturally you give, and then you give some more, and then you give to the point of breaking, and then and only then it gives back, so bountifully it overfills not only your root cellar but also that parched and weedy little patch we call the soul” (5).

It is, of course, at this crossroads of work and reward that the love stories converge. The final harvests of the first year of the farm’s life coincide with Kristin and Mark’s wedding day, a celebration held at the farm. The celebration occurred despite the fact that many wedding-related projects either fell by the wayside due to the business of late summer, were completed at the last minute, or proved more difficult than anticipated (including convincing the chickens to roost somewhere other than the loft, also the reception space).

Seven years after that day, Kimball reflects, “When I think of it now, I can see that our wedding day was exactly like our marriage, and like our farm, both exquisite and untidy, sublime and untamed. What I knew even then, though, in the middle of the chaos, was that the love at its center was not just the small human love between Mark and me. It was an expression of a larger loving-kindness, and, when I remember it, I have the feeling of being held in the hands of our friends, family, community, and whatever mysterious force made the fields yield abundant food. It is the feeling of falling, and of being gently caught” (249).

The Dirty Life provides a welcome and moving glimpse into that space of chaos, toil, love, and community.

Photo of Kristin Kimball courtesy of Deborah Feingold.

Merie Kirby grew up in California, moved to Minneapolis for grad school, and after getting her MFA stayed for fifteen more years. She now lives in Grand Forks, ND with her husband and daughter. Merie writes poetry and essays, as well as texts in collaboration with composers. She also writes about cooking, reading, parenting, and creating on her own blog, All Cheese Dinner. Her most recurrent dream is of making cookies with her mother. This is an excellent dream.